1. Is Lacan’s full speech a performative?

This thesis was defended by Mikkel Borch-Jacobsen in the fifth chapter of his book Lacan-Le maître absolu, entitled “How to do nothing with words,” a chapter in which he proposes to reconcile the Lacanian theory of full speech with the Austinian category of performative. Borch-Jacobsen suggests that the accomplished or successful speech that Lacan calls full is fundamentally performative. According to Borch-Jacobsen:

It doesn’t take long to realize that Lacanian “full speech” has all the essential characteristics of the “Austinian performative. [1] For my part, I have a few reservations about identifying – without further nuance – the definition of Austin’s performative with the full speech of the early Lacan.

What exactly does Lacan mean by full speech? He defines it in opposition to empty speech, which is characteristic of speech that is confined to the role solely of conveying what it signifies. Full speech is the occasion to displace the centre of gravity from the process of recognition, from the Kojevian specular duality of the mirror stage to the symbolic big Other.

In Lacan’s early work, the big Other is the structure that symbolically institutes the subject’s place in an established order with that signifier that pre-existed him. The big Other is the place where a system of determined relationships between signifiers is put into place, and it is in the heart of this system into which the subject will be integrated as the subject of the signifier the moment he enters into language. By this operation, the subject enters into a relationship of dependency vis-à-vis the big Other, a demand for elucidation of the unconscious symbolic mandate in which he has invested himself from the moment he entered into the symbolic-linguistic interaction with the Other. The questions “who am I” and “what am I?” can only find their resolution in the elucidation of the Other’s desire, which presents itself to the subject as an enigma.

From this point the fundamental idea developed by Lacan (according to which the decoding of the relations into signifiers consciously mobilises into verbal utterances but rises unconsciously from them) inscribes itself in a more global fashion in the elucidation of the meaning of another desire in which the subjective desire finds itself taken up: to be primordially recognized as a subject: “This is why the Other’s question (la question de l’Autre) that comes back to the subject from the place from which he expects an oracular reply is the question that best leads the subject to the path of his own desire.” [2] The reply always takes some such form as Chè vuoi? “What do you want?”

This means that, from the time he begins to speak, that is, to enter into language, the subject must subscribe, in spite of himself, to a symbolic pact whose texture will always escape him as long as he adheres to conscious speech, that is, what Lacan calls empty speech.

The big Other recognizes the subject, and it is this recognition – which derives from a symbolic pact sealed with him, and despite him — that institutes the subjectivity which, in order to recover his true self beyond empty speech, he needs in order to understand how he has been recognized, to comprehend the modalities by which he makes himself known – in other words, to learn which previously-created symbolic pact his subjectivity has adhered to from the moment it has entered into language. The big Other thus defines itself minimally for Lacan as the position from which a subject fixes, by recognition, the symbolic position of another subject.

This explains the two paradigmatic examples Lacan uses to describe full speech: “You are my wife” and “You are my master.” Full speech intervenes when the subject sees itself as having been recognized by an Other, a recognition that puts it into a subjective relation to the big Other. This explains the reason why, as in Lacan’s famous phrase, “(h)uman language… constitute(s) a kind of communication in which the sender receives his own message back from the receiver in an inverted form.” [3] Full speech supports the state of the following fact: the symbolic or illocutionary range of speech emanates from a source that is not in the subject, but in the big Other, who is positioned behind what Lacan calls the “wall of language”.

What Austin calls the illocutionary force of speech, that which does rather than describes, comes from the Other. It is received by the subject without its awareness, to the degree that it believes (or, rather, mistakenly believes) the illusion that the source of the illocutionary value of its message arises from his own ego, or from that which the Gricean and neo-Gricean would call his intentions of discourse. [4] This lack of awareness of the source of the illocutionary force of its statements belongs to the empty word in which the subject remains powerless to recognize that the establishing symbolic force of his speech comes from the big Other; for example, in paradigmatic declarations such as “You are my master” or “You are my wife”.

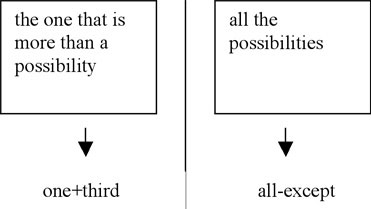

The real question is to know whether full speech is tantamount to what Austin, in How to Do Things with Words, calls a constative utterance or a performative utterance. That is, does full speech translate my adherence to a symbolic pact that links me to the big Other in a constative way (verifying a symbolic pact that has forever defined me in my subjective position)? Or does it link me in a performative way (instituting the big Other as the master by whose intermediary it will be possible for me to elucidate what is my desire).

At first glance, it would seem that full speech represents a constative that the subject must assume. Indeed, it is the big Other who made me a disciple before I could interiorise the symbolic scope of the accomplished act. Thus the speech, “You are my master” is in no way constitutive because it is the inverse of “I am your disciple”. That is, it is a constative utterance, as it does not do anything to the other except the fact that I am testifying to the Other that I have interiorized the symbolic institutive act by which I have been recognized as a disciple. In full speech, I can now assume the subjective position of “disciple” which was conferred on me by the Other. The big Other established me as a disciple” and full speech only endorses and does not realise a symbolic relation from which I merely take on meaning as subject.

My subjective position thus depends on the symbolic act by which I was put in the position of a disciple. The utterance, “You are my master” accomplishes nothing, because its truth is in “I am your disciple” – that is, not in the realisation of a symbolic pact, but in the constative recognition of its institutive scope. One could therefore defend a thesis according to which “you are my master” is thus a falsely performative utterance that accomplishes nothing, but, on the contrary, assumes that which has already been accomplished at the level of the Other.

Full speech is therefore not performative speech; it has no other jurisdiction over the founding of a reciprocity in the recognition (and not letting that recognition remain unilateral) of the fact that the subject may receive his message from the Other without assuming that that is what it is, in continuing to falsely equate the symbolic efficacy of his speech to the discursive intentions emanating from its Self. Deep down, taking “You are my master” as a performative would be a lie; it would embrace the false belief that the symbolic scope of one’s discourse derives its source from the ego, and not, as has forever been the case, from the big Other.

In full speech, the subject himself assumes the fact that he only takes his position of subject; that the grounding act is not engendered in him, that it does not actually come from him. In full speech, the subject recognizes himself as a subject. This means that he recognizes the symbolic value of the grounding act by which the big Other recognizes him as a man, or as a disciple. Similarly, “You are my wife” signifies: “I have indeed received the message coming from the Other by which I am recognized and symbolically set in place in the subjective position of husband, and I testify to this in confirming the Other in its grounding act.”

In full speech, recognizing oneself boils down to recognizing the subject Other by whom I am recognized as occupying a determined subjective position in a symbolic pact. The question is knowing whether this second recognition is performative or constative. In my opinion, the question is difficult to resolve from Lacan’s texts. One can suggest two interpretations: If we take up the logic of full speech, the sentence “You are my wife” becomes the inversed statement of the “I am your husband” that emanates from the Other. The sentence “you are my wife” thus confirms the Other as the juridical grounding of my symbolic subjectivity.

The sentences “You are my master” and “You are my wife” thus do not seem to be performatives, but rather constatives that cognitively increase the grounding (performative) act, which previously positioned me as a symbolic subject.

“The sentences ‘You are my wife’ or ‘You are my master’ mean ‘You are still in my speech, and I can affirm it only in taking the speech to where you are. It’s up to you to find there the certitude of what I am engaging.’ This speech is a speech in which you engage yourself. The unity of speech as founder of the position of the two subjects is here manifested.” [5]

However, this public speech in the place of the Other indeed has effects. It is, of course, the flip side of the observation that “I am a disciple” or “I am a man”; it is an observation that, Lacan tells us, affects my return to myself as a subject through the fixation of the Other as a principle of symbolic subjectivity. Full speech seals a symbolic pact that precedes the subject in order to constitute it in its position as subject. It causes the subject to leave the ignorance in which he was plunged concerning the pact which has forever linked him as a subject of the big Other. But for Lacan, this departure from unknowing in which the subject maintains itself by its adherence to ego does not only support a cognitive recapturing of self identity; Lacan presents it in a number of passages as itself constitutive of subjectivity: that which complicates the task of finding out whether full speech is constative or performative.

On the one hand, full speech seems not to be an act of language; its role is, rather, to make explicit the symbolic pact that has always constituted subjectivity, and which the subject turns away from in the inauthentic issue of ego. The passage from empty speech to full speech seems to assure the transition from a badly formed pact (because it remains in the state of an implicit performative on the part of the subject and not recognized as that by the latter), to that of a pact improved because its terms are explicit. In this regard, it would seem that Lacan follows the idea of pragmatic progress that Austin developed in How To Do Things with Words concerning the passage from the implicit to the explicit performative.

However, Lacan’s explanation (which is quite different from Austin’s) would seem to have the value of a constative elucidation about the Other’s desire contained in my own speech: one would move from a state of ignorance to a state of knowledge, in the transition from an unconscious implicit performative arising from the Other to its conscious assumed clarification.

To state it in Austin’s terms, full speech compensates for an initial procedural flaw relevant to his ‘Gamma cases’: the act has, from time immemorial, “misfired”. However, as Austin states, the fact that the act is hollow does not get in the way of the effectiveness of the act. For what Lacan calls empty speech is not what Austin calls the empty act; it is more what Austin would call the hollow act, that is, an act effectuated by an insincere speaker who does not subscribe to the act in the first person. [6] This is what happens in the case of a promise that the speaker knows he does not mean to keep. However, the fact that the speaker is insincere does not prevent the act from being realized, nor the promise from committing him independently of his intention to honour it.

Lacan similarly states that, in empty speech, the symbolic pact linking the big Other to the subject could take place, but would turn out badly in the case where it is not explicitly assumed by one of the parties to the contract. The psychoanalytic cure should therefore consist in correcting the procedural deficiencies that characterise empty speech, because this empty speech (that Austin calls “hollow”) engenders the symptom of which the cause is related/need be related to the fact that the subject claims to be incapable of understanding the signification of psychic pain in the Other. This lack of understanding is due to the subject’s not having previously recognized the place from which the performative significance of the signifier, that is to say its symbolic value, could be decoded.

The symptom in its iterated form translates the failure of the cognitive recapturing of a performative of which the symbolic value (coming from the Other) remains inaccessible to the subject. It winds up being what Austin calls an infelicitous act, that is, not an act that has failed, but an act for which the responsibility was not assumed. Indeed, the symptom picks up the manifestation of a signifier that asks to be integrated into the symbolic valence from which it remains half excluded by unilateralism: the grounding act emanating from the Other does not respond to any reciprocity.

If the symptom were completely excluded from the symbolic sphere, there would be no symptom, no problematic manifestation of suffering. If it manifests itself, it is because, although the signifier has indeed been symbolically founded, the institutional procedure remains badly cemented. The encounter with the big Other – to which the psychoanalytic enterprise must lead – does not thus have any other objective than to bring to completion a symbolic contract that has been badly carried out; in responding to what Austin called Gamma cases. It is why Lacan remains very Austinian on this very point, decidedly more so than Derrida, [7] since for Lacan, just as for Austin, an act not subjectively assumed has indeed taken place. The fact that it was accomplished without the subject intentionally adhering to it takes nothing away from the fact that the act has taken place. Otherwise, the theory of the unconscious would be impossible to justify.

Similarly, for Austin, a promise made without a sincere intention to keep it is still a promise. For Lacan, a symbolic contract without a subject to explicitly assume it – the subject being able to turn away from it in the inauthentic outcome of the ego – still remains an accomplished agreement, even if the subject who receives it is ignorant of his deep participation.

Full speech is, in this respect, comparable in every aspect to Austin’s act of fully accomplished language (responding to all three Alpha, Beta and Gamma cases), where one promises with sincerity, in fully assuming the act of language thus accomplished from the place of the Other. Full speech should be the realisation of the gamma condition Austin posited in How To Do Things With Words. Thus it would not have performative value. Indeed, the grounding act would always have already taken place, its bilateral rectification remaining a procedure of cognitive recuperation, in no way a performative. Full speech remains the constative and reflexive redoubling of a primordial performative having established the symbolic valence of the subject even before it has been assumed. As Austin would say, it exhibits a disposition to sincerely accept speech coming from the Other, to no longer shrink from the implications nor from the verdict of such speech.

In this regard, one could read things in two ways, and it seems to me that Lacan did not define this issue. One could say that, for Lacan, an explicitly-rendered performative remains a constative; i.e., a personal adherence to an act which did not take place on the part of the Other. One could also believe (and certain pronouncements of Lacan on the matter open up this possibility) that, just as in Austin, the explicit performative does not turn up a constative reduction of the performative, but a pragmatic amelioration in the realisation of the act: the passage from empty speech to full speech would correspond to Austin’s description of the passage from primitive to explicit forms of the utterance. As Austin states:

(P)rimitive or primary forms of utterance will preserve the ‘ambiguity’, or ‘equivocation’, or ‘vagueness’ of primitive language in this respect; they will not make explicit the precise force of the utterance…. Language as such and in its primitive stages is not precise, and it is also not, in our sense, explicit: precision in language makes clearer what is being said – its meaning: explicitness, in our sense, makes clearer the force of the utterances, or ‘how it is to be taken’. The explicit performative formula, moreover, is only the last and ‘most successful’ of numerous speech-devices that have always been used with greater or lesser success to perform the same function (just as measurement or standardization was the most successful device ever invented for developing precision of speech). [8]

Austin’s explanation makes it clear that there should be an effect of self-realisation that should not stop before full speech. The explicit act should improve the symbolic scope of the original act in removing all equivocation on its value, such that the act should accomplish what it was not able to do in its primitive form, that is, the formation of the subject. Under the effect of this explanation, the performative would be even better realized to the point that it would put the subject in the position of no longer being able to escape the judgment of its symbolic destiny pronounced by the big Other. The impact of the explicit performative should be to clear away all equivocation in the reception of the act; it should have the effect of giving it more scope, improving the transmission of its illocutionary scope of which the realisation itself is a constituting act.

One could thus ask oneself if full speech does not dispose of this capacity to retroactively act upon the initial message in permitting it to realise itself a second time, in a more complete fashion. Thus the removal of symptom would reside in this amelioration in the realisation of the act The question is, therefore, to know whether full speech remains determined by the descriptive exigency of comprehension of the symbolic value of the constituting message emanating from the big Other, or if, on the contrary, it has a performative secondary scope capable of allowing the performative emanating from the big Other to completely realise itself, to completely unfold itself, something that was not possible so long as it remained implicit. In this way it should allow the subject to receive the message that comes from the Other without the possibility of denying it, without ambivalence or equivocation.

In reality, Lacan’s texts on full speech, together with Austin’s, allow the formulation of one or the other of these two hypotheses. What is clear is that for the Lacan of the early 1950s, the presence of the symptom proved that the act had already taken place, but in a vague, non-explicit fashion. However, is it the case that the explanation of desire of the Other as a constative act enables a curative virtue or, on the contrary, is it, as a second performative act, ameliorated retroactively?

In my opinion, the two hypotheses can be supported to the degree that the subject assumes the symbolic relationship that has, since time immemorial, linked him to the Other, where he institutes the big Other by confirming him in his position of authority. This confirmation allows the foundation of the big Other’s absolute position, which permits the subject to fix himself to the purpose that comes to him by means of his symbolic recognition by the big Other.

Indeed, Lacan affirms: “In the end, the speech value of a language is gauged by the intersubjectivity of the ‘we’ it takes on.” [9]

Thus empty speech would oppose itself to full speech only by virtue of the fact that in it the symbolic contract would be carried out in the impoverishing mode of denial, of refusal to understand. One remains with full speech from the point of view of the constative sense to the detriment of the act. Full speech returns to assume the fact that the symbolic act of institution comes from the Other and not from the ego: in this sense, full speech is humbling for the subject, as he comes to realise that his position of subject does not precisely depend on him, but that it belongs to the grounding act by which the subject previously recognizes himself by the big Other. In my opinion, it is this point of view that changed, starting at the end of the 1950s (the date of Lacan’s Séminaires on ethics), from which point one observes (notably with the commentary that Lacan proposed on Claudel’s The Hostage) that the performative scope of the act cannot simply be assumed as coming from the Other. This is particularly the case concerning what I propose calling a Lacanian perlocution.

But before moving on to this point, one must respond to the second burning question in the analysis of Lacan’s development between 1953 and 1960: is the symbolic reducible to the field of ordinary conventions? Or, in other words, can one reduce the realization of symbolic acts to acts recognized by the linguistic convention that Austin would call the realization of speech acts?

2. Is the symbolic solvable under ordinary conventions?

This question seems to be resolvable from the perspective of the refinements Lacan developed in Séminaires V and VI, notably in his Graph of Desire:

Looking at this graph, one can see that the category signifier, as it exists, only represents a diachronic sequence of signifiers. The chain’s anchoring to the big Other ensures the passage from the signifiers’ mere fluttering to the recognition of the symbolic and holistic value of each signifier in relation to the entirety of the system to which it belongs: the recognition by the big Other, or linguistic code, thus ensures the signifier’s movement from diachrony to synchrony. The big Other represents the “button tie” (point de capiton) [10] that stops the wave of signifiers in order to transform the entirety of their relations into one structure. It is the double retroactive effect created by the intervention of the big Other on the signifying chain that, for Lacan, explains the value of the sign as described by Saussure.

By itself the signifier does not articulate itself at any determined signified. For the relationship to consolidate itself, there must be a supplementary intervention on the part of the big Other, which is the only power capable of temporarily stopping “the otherwise indefinite sliding of signification” [11] under the signifier. Beneath the meaning, there is the non-meaning of the signifier, upon which the big Other’s grounding and retroactive action applies itself in the “second pass”, the big Other being itself a generator of signification. It is due to this original non-coincidence of the signifying chain of the big Other (as the operator grounding the sense) that Lacan in Seminar V defined the signifying chain as metonymic; that is, capable (beyond its conventional fixed signification) of creating new meanings that overflow the field previously normed by convention.

The first level of the graph, that of the signifying chain, can always, as in the case of slips of the tongue and witticisms, reassert its rights and engender new significations, because the signifying chain remains fundamentally refractive to every definitive signified fixed meaning. However, the coherence of Lacan’s system requires the big Other to be at the receiving end of such meaning-creation. In this configuration, the big Other can no longer be likened to a conventional code as is the case in rational discourse. One can identify the big Other at the first level as the representation? of a conventional code that ensures the realization of ordinary speech acts. Lacan considers these to be the poorest element of the signifier; he calls this conventional speech “repetitive purring pure and simple, like a mill of words,” [12] inevitably leading the subject to the deprivation of the imaginary fixations of the ego. The symbolic foundation of the subject in the conventional system elevates the movement by which a subject makes himself known by his correct usage of pragmatic conventions such as the speaker or agent of discursive intentions, constituting the contents of the mobilized signifying sequence.

Here one sees the reduction of the signifying chain at the point of transmission of an intentional message, where the pragmatic field of validation is defined by the codes of convention (situated upstream from the speech acts). However, Lacan considers this “ordinary” encounter with the visage of the big Other (here reduced to what Austin calls the A1 condition), that of the pragmatic of the illocutionary, to be no less the poorer. In this configuration the big Other constitutes an imaginary subject, a subject who is under the illusion that the illocutionary value of his statement is located in his conscious intention to say something. He misconstrues the fundamental operation from which the conventional and intentional scope is derived, that is to say, his heteronomic dependence on a grounding Other, irreducible to a code, and by which his recognition of what it is conditions full speech.

For Lacan, reducing the figure of the big Other to the conventional code only establishes the imaginary subject in the restrictive signification of the symbolic value of the signifying chain. The field of the Other overflows that of the conventional code. This is the objective of the Séminaire V, to show that what the conventional system would sanction as failures at the illocutionary application level does not, however, condemn the symbolic scope of the act performed, in cases such as slips of the tongue or witticisms.

The profundity of Lacan’s thesis is situated here, in his refusal to reduce (as Austin would do, and with him Searle’s ‘intentional pragmatics’) the symbolic to the sole field of convention: acts of language exist that remain null on the conventional plan, but which are absolutely not, however, empty from the point of view of their Symbolic value. The Symbolic efficiency of language has been defined by Lacan precisely as to be able to overflow the conventional field, to surpass its criteria of validation – those of ordinary usage – and thus not permit their ‘neutralisation’ in considering as null (which would be the case with Austin) the scope of acts as paradoxical as slips of the tongue and witticisms. Austin, on the other hand, considers as failures those acts he calls defective, and which he places in the category of ‘misexecutions’ applicable to his B cases (that the procedure of carrying out the language act took place, but it failed because it was not accomplished). [13]

Lacan takes up this idea again in Seminar V, where he discusses the famous example studied by Freud in Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, the construction of the neologism famillionaire by Hirsch Hyacinth. Lacan suggests elucidating the mechanism of this formation by considering the signifier as a psychic rule. He illustrates in his Graph of Desire the ramifications of the movement of the signifier in two signifying chains – conscious and unconscious – simultaneously mobilized in the subject’s speech This division allows Lacan to make the case that the subject never knows what he has done with the signifying sequence that he has marshalled: the illocutionary value, that is to say the identification of what the speaker does with words, remains hidden for him as long as he is unable to make the big Other – likened to the code of ordinary language practice – recognise anything other than the sole chain of discourse. Indeed, the chain of discourse would not be able to realise the illocutionary value of a linguistic performance by sole virtue of the fact that every linguistic performance activates the simultaneous deployment of two signifying chains What remains at stake is the ability to capture the value of the enunciation beyond the sense of the utterance, in order to elucidate the fully symbolic illocutionary range of the linguistic performance:

Does he himself (the speaking subject) know or not what he is doing in speaking? Which means: is he able to efficiently signify his action of signification?”

It is precisely on this question that we may divide these two levels, of which we must consider that they both function at the same time in the slightest act of speech. [14]

This ramification, introduced by the graph of a word divided into two signifier circuits, has a decisive importance: it shows that the problematics of desire, woven into those of language, forbid reducing the latter (the language) to the mere pragmatic relationships of conventions to accomplished acts for the purpose of understanding it’s (the language’s) symbolic reach (first level: DS vector, where the accent is on s(A) on the s of the signified in contrast to the S of the signifier).

The problem of a perspective centred on ordinary discursive patterns would constitute just too great a restriction from the point of view of the Graph of Desire. It would presuppose the possibility of analysing a language free of the symbolic complications that its relation to desire inevitably introduces: reducing the symbolic to the conventional would thus destroy the inherent complexity in the field of the signifier. This complexification would therefore end up deactivated, revealing a language restricted to its relation to the code and to the rationality of the illocutionary functioning correlated to it.

However, according to Lacan, this reduced perspective of language could still be valuable if one adopted a dualist perspective of the psyche, so that, in the end, the conscious and the unconscious would belong to substantially compartmentalized spheres. Such a compartmentalisation would, of course, allow the isolation of the logical from the illocutionary sphere, and would therefore dismiss as failures such hybrid formations as slips of the tongue or witticisms.

By its treatment of the psyche’s wholeness at the exclusive level of the signifier, the Lacanian perspective does not reduce it to a uniform monotony, reducing everything to the same linguistic plane, because the field of the signifier has the characteristic of dividing itself into two circuits, implying at least a symbolic bivalence (represented by the two levels of the Graph of Desire), and attaching two signifying chains to each other – the unconscious and the conscious chain – under the same signifying denominator. For Lacan, the duality of the signifier does not imply a substantial difference between the conscious and the unconscious. This duality takes shape in the single element of the signifier, which Lacan later explained in his discourse on the topology of the Moebius strip.

On the Graph of Desire, the unconscious chain (vector D’/S’ on the graph) extends the conscious chain (vector D/S) with no discontinuity between the two chains. As shown by vector S(A)/s(A): a conscious signifier (represented by its signified) replaces an unconscious signifier from which it, in reality, derives its real value (because the signifier only holds its value from its relationship to another signifier). This explains the possible parasitic contamination of the conscious chain by the offshoots belonging to the unconscious chain, thus accounting for the formation of slips of the tongue and witticisms.

Just like a Moebius strip, the Graph of Desire supports the double inscription of the conscious and the unconscious chain in their common belonging to the homogenous field of the Symbolic in so far as the latter collects them both at the same time. In Freud’s Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, the anecdote of the neologism famillionaire is demonstrated in the following manner: Salomon Rothschild had welcomed Hirsch Hyacinth by treating him as an equal; it was this fact that Hirsch Hyacinth had the primordial intention to announce.

Instead of saying, “He treated me familiarly (as a family member)” Hirsch Hyacinth blurted out, “He treated me (as a) famillionaire.” Lacan presents this verbal event as the product of a condensation between two signifiers – familière (‘familiarly’) and millionaire. The presence of two phonemes in common (mil/mille and ère/aire) leads to a “kind of collision” between the two signifying chains.

The signifier, as we have seen, is produced by the encounter of the signifying chain (Δ/Δ’) with the circuit of discourse passing by A (= the big Other) and arriving at γ, which functions as a nodal point retroactively conferring its signification (in an intention to make sense) to a mobilized signifying chain relative to code (A). Which implies that, in order to wish to make sense, it is first necessary for the subject to receive his own message from the Other. For Lacan, this is the property of every signifying engagement: the subject always receives his own message from the Other.

Here, in its willingness to make sense, the intentional act is not like the classic phenomenological device located upstream from meaning, but downstream from it: in wanting to make sense, it comes back to elicit his own message from the Other, for the Other constitutes the reserve of normed linguistic performances that it is possible to utter. Wanting to make sense comes back to asking oneself at the start what makes sense, to take up a procedure already recognized and thus stabilised as conventionally acknowledged by the big Other. The realization of a speech act is not only the actualisation of a procedure received by the subject from the Other. Here the procedural specificity, such as one finds in Austin’s conventionalism, conditions the possibility of wanting to say something.

Just as with Austin, the intention to make sense does not suffice to realise the speech act. (For example, I could wish to baptise a penguin, but my intention will fail if it does not fall under a convention that would authorize it, and no such convention exists for the baptism of penguins.) It depends on its conformity to conventional procedures linked to an applicable context. That is signified in the path of this graph, the fact that the speaker begins by receiving his own message from the Other even before he performs it as an act of language. The circuit is the following on the graph: the message leaves Α and arrives at β (the place of “I”) in order to return to Α, which brings a halt to the sequence of signifiers mobilized on the signifying chain Δ/Δ’. Thus γ is the place where the message is concluded. If the signifying chain were to bring to completion its symbolic formation from the single place of the code, the message in γ would have been “He treated me as an equal, as a familiar.”

However, and according to the complication introduced by the potency of desire over the signifier, the symbolic spills beyond the field of the single formula, which formalizes the vector β/β’ on the graph.

However,” Lacan warns us, “do not forget that the interest of this schema is that there are two lines, and that these things circulate at the same time on the line of the signifying chain. [15]

What does this mean? It means that the signifying chain (vector Δ/Δ’) translates what arrives from β’ into a signifier. β’ is the point of the metonymic object that nourishes the chain of discourse, of excess signifiers with respect to the code. Indeed, if one limits oneself to the stoppage of the signifying chain by the single code, one should obtain the product familiarly in Γ. However, the result here is instead famillionaire, which means that an external signifier has interfered with the process of signification. The signifier is millionaire, and comes from the point B’, which stores the metonymic object of desire of Hirsch Hyacinth, that is, my millionaire. The object is metonymic in that it reveals the desire that Hirsch Hyacinth, as a lottery collector, can neither admit nor achieve: having a millionaire to mitigate his financial problems.

From the point of view of the big Other, the symbolic place of Hirsch Hyacinth is clearly defined: he is stopped at the point de caption by the big Other as being owned by the millionaire Salomon Rothschild, rather than the other way around. The object of desire is therefore repressed as being completely fantastic in the social milieu to which Hirsch Hyacinth belongs. For this reason the object finds itself engaged in a parallel circuit that collides with the obtained signifier γ (the place of the message). Thus while the desirable object my millionaire is repressed, the B/γ circuit remains open such that the metonymic signifier succeeds in ‘hacking’ the message to the point of encounter between two common phonemes (ère/aire and mili/milli) and the two signifiers thus condensed into the neologism famillionaire.

The excess of the symbolic system on the code (by means of the signifying circuits introducing the dimension of desire inherent in every linguistic performance) is not considered by Lacan, as would be the case with Austin, which deemed it a failure of procedure. On the contrary, it reveals the infinite reserve of meaning of which the signifying chain is capable, as well as its capacity to create new meaning beyond those already fixed, expected and foreseen by the conventional code. Convention always lags behind the fertility of the signifier; it catches up only after the fact in the systematic codification of the novelty that it introduces.

This novelty raises the issue of what Lacan calls in L’envers de la psychoanalyse “a knowledge that does not know itself”; that is, a knowledge that does not find confirmation of its conventional validity in the big Other. [16] But here is the fundamental point upon which I wish to insist (and Seminar XVII marks a turning point in this point of view): Seminar V remains conditioned by Hegelian/Kojevian logic of recognition, and does not approach the distinction Lacan proposed in Seminar XVII between “a knowledge that knows itself” (i.e., a knowledge confirmed by the big Other) and “a knowledge that does not know itself” (i.e., a knowledge not supported by the confirming validation of the big Other) and whose characteristic is, once introduced, to disrupt the parameters of the code from the utterance of a signifier whose value is situated in an excess that the symbolic system (the big Other) does not know how to contain.

I propose here to show that Lacan’s Seminars on ethics (i.e., VII and VIII) from the late 1950s and early 1960s open the possibility of language acts not recodifiable by the big Other, acts overwhelming the logic to which Lacan held until 1956 (that is, the Hegelian/Kojevian logic of recognition). It is this logic that is, it seems to me, profoundly subverted in Le transfert, and I will attempt to show how.

In Les formations de l’inconscient, Lacan placed the big Other’s recognition of the value of the linguistic performance at the horizon of meaning-creation that overflows the normed field of convention. The subject of desire is recognized by the big Other as a desiring subject, that is, as a symbolic subject of which the conventionally failed performance pronounces a message beyond the “purring” of discourse.

In Seminar V, Lacan is still influenced by the Kojevian dialectic of recognition, and places the figure of the big Other as the agent by which the subjectivation of the desiring subject realises itself under the effect of his recognition by the big Other. The model thus proposed introduces the possibility for the ‘creator acts of meaning’ to overflow the field of convention, but never that of the big Other, nor of the symbolic recognition that he systematically accomplishes from the moment that speech begins. The symbolic value of the created linguistic development, and of the desiring subject who supports that development, depends on the big Other’s recognition of its signifying scope (and this despite the appearance of failure at the pragmatic level of the codified performance).

Every speech act, even if creative, must receive its value from the recognition that the big Other is capable of according to it. However, the behaviour of the dialectic of recognition as principle of identification of the symbolic value of a signifying sequence beyond convention obliges Lacan to maintain the lexicon of convention as the paradoxical model of all the forms from which the recognition proceeds. It is, in effect, a question of thinking of a certain type of paradoxical message identifiable by the big Other beyond the code:

The message (that of the famillionaire) is perfectly incongruous in the sense that it is not received, it is not in the code. Everything is there. Certainly, the message is created in principle to be in a certain distinctive relationship with the code, but there, it is even at the level of the signifier that it is manifestly in violation of the code… The message remains in its difference from the code. [17]

In other words, the symbolic recognition, while establishing itself in its difference with validation by the code, does not cease to extend the model: it is always a question of a message that is dependant downstream of the big Other as an instance of symbolic validation of the realized linguistic performance. The big Other must convert that which appears to the code as a failure into a successful message: the analyst must recognize a message, and authenticate it as it is cleared to proceed to a recodification of the code:

How is this difference sanctioned? It is now a matter of the second level. This difference is sanctioned as a witticism by the Other… The Other sends the ball back, it stores the message in the code as a witticism. It says in the code: This is a witticism. If no one makes it, it is not a witticism. If no one perceives it, [18] if famillionaire is a slip of the tongue, that does not make it a witticism. The Other must codify it as a witticism in order for it to be inscribed in the code by the Other. [19]

It is this mechanism that Lacan profoundly modified when he developed an ethics of speech acts, a modification that would make it no longer able to guarantee the recodification of an unconventional sequence, as it was still the case in Seminar V. At that point in time, Lacan sketched out a plan wherein the speech act is systematically recodifiable; thus every speech act is characterized by the fact that it systematically disposes of a symbolic value, even if it is in excessive in relation to the linguistic code. It is evident in his Seminars on the ethics of desire that Lacan has opened the possibility of real acts, that is to say of acts not allowing any recodification of the code, of acts capable of overflowing the field of the big Other. Until 1960, the model remained the problematic one of an omnipresence of meaning, of a cognitive omnipotence of the big Other, through its capacity to recodify the code; a capacity that could be endlessly adapted to every type of signifying formation, by extension of the code to the format of all possible symbolic performances engendered by the subject.

The question that remains to be asked is, how do we identify the active component in the signifying chain of language as an act, properly speaking, that would no longer depend on the big Other? In other words, how do we identify the layer of the act that no longer depends on its symbolic value? I tried to show that in Seminar V it took its inspiration from the conventional model without, however, managing to truly overcome it. The question is thus to know whether Lacan managed to think of the speech act not only as a symbolic performance, but also as a real accomplishment. In other words, is there a place in Lacan for thinking about the perlocutionary dimension of the performative, the language act as Real? (At that point in time, the question of knowing what was necessary in order to understand the “Real” was yet to be resolved.)

In Austin, the duality between the illocutionary and the perlocutionary is explained by the fact that the liaison of the speaker to conventions is not isolatable from the exterior reality of the circumstances that inscribe themselves on our discourse. This inscription has a double implication for Austin:

1. That our acts produce non-conventional consequences on the interlocutor: perlocutionary effects. [20]

2. That our acts are rooted in a reality based in circumstances that can be reduced neither to meaning nor to the conditions in which they take place. When an act fails, it can thus be explained, in part, by the indifference of the real to the symbolic part of our experience.

We have seen that in the Lacan of Seminar V there is no place accorded to the Real, that is, to a part of the act that could maintain itself outside the symbolic sphere. As we have seen, the big Other revealed itself capable of absorbing and of recognising each and every linguistic performance, including those characterized as failures from the pragmatic point of view. Nothing would seem to escape the big Other; i.e., the symbolic recognition of any signifying sequence mobilized by the subject. Whereas for Austin, the speech act engenders non-symbolic effects to the degree that it is itself composed of real circumstances necessary to its execution.

Before Le transfert, Lacan was not really interested in the Real of the act; that is, in that which was outside the realm of the symbolic. Which implies the following fact: although in Les formations de l’inconscient Lacan speaks of speech acts in order to evoke the utterance, the reference to Austin remains implicit and badly developed, insomuch as every speech act always carries a message that has already happened in the Other, including the cases of acts of meaning-creation. However, the Real, for Austin as well as for Lacan, in meanings that cannot be likened to each other (to which we shall return later on), is that which in the act does not pertain to the symbolic order; it is unable to make any symbolic recognition of the object. The transformation of this mechanism is, I believe, proposed in Lacan’s discussion of Claudel’s The Hostage in Le transfert. This transformation allows us to re-read the Graph of Desire in a completely new way, in order to understand the ways by which the perlocutionary act arose in Lacan’s thinking as the blind spot of the symbolic, the Real of the speech act.

Indeed, in Austin, the perloctionary dimension of the act is the objective witness of its belonging to the reality of circumstances as they remain irreducible to the symbolic/conventional dimension of speech. For Lacan, the perlocutionary act is as revelatory as the Real, but it must be understood in a Lacanian sense: that is, not what is found to be ontologically distinct in the symbolic, but rather as that which the symbolic is powerless to contain. That is, as the thing that radically escapes the symbolic recodification engendered by the infinite enlargement of the powers of recognition of the big Other, the Real manifests itself as the hole that resists the totalising absorption of the recognition of the symbolic value of a linguistic performance made possible thanks to limitless recodifications executable by the big Other. The inauguration of the act in this internal failure at the symbolic level reintroduces a traumatic perlocutionary performance whose impact should be measured. This perlocutionary dimension shares with Austin the fact that it includes the non-symbolic performance of the accomplished speech act. However, in contrast with Austin, the Lacanian perlocutionary is not content with having causal effects on the interlocutor, but rather traumatic effects on the entire symbolic system.

In other words, where Austin firmly separates the two layers of illocutionary and perlocutionary acts, the Lacanian mechanism allows us to think of the incidence of the Real on the Symbolic itself, for the simple reason that Lacan describes the Real not as that which is beside meaning and in which meaning inscribes itself in order to realise itself. Instead, Lacan’s Real spells from the intimate fault line in the symbolic system.

For Lacan there is a perlocutionary, or Real, performance, not because another system would exist – that of causes, the causal/natural network – alongside symbolic efficacy as would be the case with Austin), but rather because there exists a dimension of linguistic activity that resists all symbolism. At this stage, it is a matter of evaluating the type of perlocutionary performance that introduces such a hole in the symbolic system, and the type of ethical performance that makes it attainable.

3. What is the Real of the Speech Act?

The novelty that Lacan introduces in Seminar VII is that the scope of an act must be considered in its spillover in relation to the symbolic. This thesis is also developed in his Ethics of Psychoanalysis.

1. The desire of the Thing, beyond the Symbolic.

It is through a re-reading of Freud’s Outline of a Theory of Practice that Lacan opens the topic of an original account of maternal satisfaction, always and forever unavailable to symbolism.

The impossible access to the Other, as every Other, as absolute Other as Thing, has the effect of creating a demand that it takes as an object. However, a gap intrudes in the transfer of the request to the Thing, in the sole measure where the signifier seeks to name that which is not nameable. The goal of the signifier remains marked by its non-conformity to the non-symbolic dimensions of the Thing, in such a way that the process of the request finishes by digging an ever-widening gap at the Thing, itself implying the interminable reiteration of a demand that sculpts, much more than it destroys, the field of its inadequacy to the Thing that it is aiming at.

In The Ethics of Psychoanalysis, Lacan takes up the Freudian distinction between the representation of a thing (Sachvorstellung) and the representation of a word (Wortvorstellung) in order to oppose both of them to the Thing (das Ding) which itself does not have Vorstellung. Indeed, Lacan insists, “Freud speaks of Sachvorstellung and not Dingvorstellung. [21]

From that time on, that which is the thing of the representation of things, its correlate, is the object in the sense of the signified. On the contrary, the Thing appears negatively as being that which representation has no hold, as that which belongs to the order of that which radically escapes it:

Sache and Wort are, therefore, closely linked; they form a couple. Das Ding is found somewhere else. [22]

In the section entitled “Memory and Judgment’ in his Outline of a Theory of Practice, [23] Freud describes the first encounter of the subject with an unknown aspect of the Other, that which Freud calls the Nebenwensch, that which one can translate, as does Lacan, as “neighbour” (prochain). Freud opposes two aspects of the “neighbour”: on the one hand, the neighbour is the other self whom the subject recognises as such by identification; he sees in the other another self. In this specular identification, a dimension of the neighbour as other is mastered.

This stage corresponds to Lacan’s mirror stage and to the imaginary identification to the alter ego that results from it. However, and this is the essential aspect of the Freudian description, there exists a part of the Other thus pierced which resists its specular integration, and which can be found in the mode of strangeness, of that in which the subject is powerless to project himself in a specular fashion. This dimension corresponds to that which Lacan will call the Real of the Other, or Thing, and it manifests itself as a unfathomable abyss that neither cognitive, nor specular nor symbolic domestication can contain. The Other in the dimension of the Real characterizes itself by its absolute impenetrability. During his encounter with his “neighbour” the subject experiences a radical ambivalence, since the heart of the identification of the subject to his neighbour surges through the gap of his radical otherness.

The Thing is thus the opening that attracts the symbolic structure to itself. It is the Thing that aims at the request without being able to attain it: the Other. This Other (the mother), who has given primordial satisfaction to the child, spreads itself out into two modalities. The first modality is the experience of the subject’s primordial jouissance by the satisfaction that the Other has been able to provide it; it is in the dimension of the Real that such a relationship of satisfaction obtained from the Other short of every demand is accomplished. The reiteration of such a primordial jouissance moves into a second stage by the procession of signifiers where the demand of the subject is articulated, but this demand is the request to obtain that which was originally obtained without asking for it; under this second modality, the subject addresses itself to the Other in the Symbolic dimension.

The figure of the Other incarnates this duality of the neighbour: at the same time it is the real source of the primordial jousissance that the subject seeks to regain, yet quest causes him to tip over the side of the second and derivative dimension of the Other: the Other as a receiver of the signifiying demand. One could summarise this situation under the following formula: what the subject searches for is the Other as Real, as Thing, and what he finds in the element of the mobilized signifier is the Other as the symbolic correlate of its demand (the big Other). A discrepancy thus intrudes between what the desire is targeting (the Other Thing) and the debased correlate obtained in place of the Thing, that is, the Symbolic response of the big Other. The subject finds himself confronting the Other as a stock of signifiers, and these signifying mechanics are substituted for the lost primacy of its relation with the Real Other.

In Lacan, the figure of the Other is located at the intersection of the Symbolic and the Real, and it is this entanglement that founds the double subjectivation of the subject of desire:

1. The emergence of the subject is carried out in the element of the symbolic as the effect of the knowledge by the big Other who addresses his symbolic mandate to him, that is, a fixed place at the interior of the signifying universe that the big Other has captured for him.

2. The ethical subjectivation which, by the intermediary of the death instinct, decides to force the restriction imposed by the Symbolic Order in targeting the Thing, that of suggesting a realm beyond to the symbolic mandate which was fixed for him by the big Other.

Here, the subject no longer aims at the accomplishment of his symbolic destiny; he targets the Thing beyond that, in such a manner that he introduces a gap between the signifier and himself in the heart of the signifying chain – the impossible substantial reflexivity of the signifier. The signifier reveals himself in such a case as a figure overrun by the desire of its subject, a subject that the big Other proves powerless to completely assign to its symbolic mandate:

We can try to define the field of the subject insofar as it is not simply the field of the intersubjective subject, the subject subjected to the mediation of the signifier. [24]

The subject targets the figure of the Other not as meaning, but as Real. It is the passage of the symbolic to real subjectivation that is described in The Ethics of Psychoanalysis. The tragedy of Antigone will become an exemplary standard for Lacan: in desiring the possible Antigone returns the symbolic order to its fundamental substantial lacuna (its lack of the Thing). But that which interests Lacan about this tragedy is what Antigone accomplishes through her fidelity to her desire: that which Lacan calls the passage from the first to the second death. This passage is completely characteristic of the modifications Lacan made in 1959 to the concept of the death drive. Since thereafter the authentic link to death is no longer simply posed as inherent to the signifier, it supposes the subjective complement introduced by the accomplishment of the ethical act. The “second death” defines itself by the extraction realized in the ethical act, of the signifying chain to its contents. The excessive desire of the Thing causes signifying chain to return to itself as an empty container. The passage from the first to the second death is nothing more than the process by which the “dumping” of the signifying chain is effectuated. The detaching of the signifier from his contents implies the dynamic articulation of two fundamental concepts:

1. The death drive by which a subject forces the homeostatic and diachronic limits of the signifier towards the Thing, in overrunning the Imaginary logic of life.

2. The eternity achieved by the signifier, and the indestructible desire that impregnates his inextinguishable character, which Lacan illustrated on a number of occasions by the expression he borrowed from the poet Paul Eluard, le dur désir de durer (“the difficult desire to endure”).

The death drive, according to Lacan, has the property to make the ex nihilo arise from the place from which the signifying chain emanates. It is on the creationist model implying an absolute beginning that it is necessary to understand the sudden appearance in the world of the signifier:

It is only from the point of view of an absolute beginning, which marks the origin of the signifying chain as a distinct order [25]

The first death thus conceives itself as a corporal, biological death; the second death is, on the contrary, the condition beyond this first death, from the indestructibility of the signifier as that which, because it arose from nothing, remains inassimilable to the ‘existant’ that supports it while it is alive.

In this instance, Antigone’s act is perfectly revealing of the movement from the first to the second death: the first death is the actual death of her brother Polynices (his corpse); the second death claimed by Antigone resides in the possibility of maintaining the status of her brother as vanished under the immovable signifier of his sepulchre. Even without a living container, the signifier of Polynices represents the eternity of his name beyond the temporary existence that he grafted to it. The timeless amplitude of the signifier does not know how to reduce itself to the life of a being that it represented during a finite period of existence.

This brother is something unique. And it is this alone that motivates me to oppose your edicts. Antigone invokes no other right than that one, a right that emerges in the language of the ineffaceable character of what is – ineffaceable, that is, from the moment when the emergent signifier freezes it like a fixed object in spite of the flood of possible transformations. What is, and it is to this, to this surface, that the unshakeable, unyielding position of Antigone is fixed. (…) It is nothing more than the break that the very presence of language inaugurates in the life of man. [26]

The emotional life of Polynices belongs to the sphere of the signified: that which fixes the existence of Polynices beyond the signified and of his ontological evanescence (his slippage indicated his disappearance into death) is the signifier. Here the figure of Antigone presents itself as the incarnation of a desire which, capable of preserving itself as the desire of nothing of the Thing, impregnates the signifying field of this emptiness, and re-articulates the Thing to its origin in the ex nihilo of an unconditioned surging out of nowhere. Here again one finds, in Lacan’s movement from the first seminars to Seminar VII, a static/descriptive to a dynamic/prescriptive perspective, the opposition between the first and the second death. Indeed this distinction was already actually present a year earlier in Lacan’s commentary on Antigone in Seminar VI, Desire and Its Interpretation. This distinction shows up again under the form of a static opposition. What is new in Seminar VII is the dimension of the act required in order for the signifier to cross from one modality to the other. Indeed, this is the difference that Lacan proposes in discussing the episode in Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe where Robinson identifies Friday’s footprints on the beach of the deserted island.

The definition of the Lacanian signifier appears with great clarity at the occasion of such an analysis. The signifier is not yet there; one considers it as a trace, the trace of a presence to which the signifier will return (in the event of Friday’s presence). If one supposes that someone had come to blot out this trace, then there is no more trace of Friday’s presence. However, Lacan makes clear that it is not in the footprints, nor even in the erased footprints, that the signifying function reveals itself. Because the signifier represents not the living presence of an individual, but rather his proper capacity to make himself disappear:

It is not the obliterated trace that constitutes the signifier; what ushers in the signifier is something that presents itself as being able to be erased. [27]

Robinson wipes out Friday’s footprints, but he leaves a sign (a cross) that marks this erasure. The signifier is this cross, this witness of the signifier as the one who has been erased. The authentic signifier represents the operation of his own erasure. He represents the erasure of that which initially represents the subject:

I told you that the signifier begins, not with the trace, but with that which erases the trace, and that it is not the obliterated trace that constitutes the signifier. What ushers in the signifier is something that presents itself as being able to be erased…. The specific signifier is something that presents itself as being able to be erased itself, and it is precisely in this operation of erasure that it exists. [28]

The “specific” signifier (that which Lacan a year later would call ‘the second death’) is the negation that represents itself as having denied its first state as representative of the subject. Conversely, the signifier represents the subject as that of whom there remains no trace, unless a trace remains to show that no trace any longer exists. This complication allows the signifier to play a supporting role of negativity to which Lacan does not cease to refer throughout his discussion of the lament of the tragic hero – Oedipus in this instance – who is overcome by the weight of a “had I never been born!” The signifier becomes the indestructible trace of negativity; it is a witness to desire as a desire of self-eradication. There remains nothing left of the subject that can attest to his presence, unless no trace remains that he ever lived.

In other words, the signifier in its primary state is free from diachrony; that is, of its link to the historical subject that he bears: in the cases of Friday or of Polynices, the signifier returns to the subject in support of their psychic purpose.

Limiting oneself solely to the diachronic ambit of the signifier risks assimilating the signifier to the signified properties that disguise it in the course of the life of an ego, rather than understanding that these same properties slip and reflect only the superficial layer that is formed above the synchronic signifiying chain. Moreover, this chain has always already constituted the subject of the Symbolic, well before it drifted to its Imaginary identity.

In this manner, the signifier finishes by merging into the first death to which Creon wishes to condemn Polynices. It is from this first death that Antigone desires to extract her brother, and it is in this manner that she incarnates par excellence the subject of desire. Because in elevating her brother to the second death, she refuses to let the memory of his life rest restricted to one imaginary individual. She wishes to bear his essence as a Subject of desire. This is why she refuses Creon’s reduction of her brother to the status of traitor of the city. Beyond the contingent determination overwhelming him from the Symbolic Order, Polynice subsists as the Real Subject, that is, as the Subject whose signifying integrity to support the Void of his desire remains inalterable.

This relationship of being suspends everything that has to do with transformations, with the cycle of generation and decay or with history itself, and it places us on a level that is more extreme than any other insofar as it is directly attached to language as such. [29]

This sole irreducibility of the signifier to each signified content demands, from an ethical point of view, the burial of Polynices, and the sepulchre marked with his Name, inasmuch as it incarnates the fundamental ahistoricity of the signifier as signifier of the subjectivity contained in its essence. Lacan discharges to the conscious the role of bearer of the subjective integrity: the signifier, while he denies himself, affirms across this negation of diachronic properties with which the time of a life is merged with the first death (the absence of the individual and the biographical memory are part of this first death), and its fundamental negativity, that is, its irreducibility to every historical signified accomplishment.

Only the movement of negativity leads the Subject back to the Truth of himself as Subject of Desire, which finds the face of his own destiny in the fundamental Void around which every desire is articulated. As the signifier represents the subject of desire, it remains refractory in its assimilation of the properties that give it its diachronic sense. The synchrony of the signifier consists in, very precisely, the fact that the it must move away from these same properties. The essence of the signifier is not in the contingent properties that cover the time a life directed towards death; the eternal essence of the signifier — as a representative of the subject of desire — belongs to its capacity to obliterate itself as a diachronic signifier. Its synchrony prevails in this very obliteration.

The synchrony of the signifier thus rests on the signifier’s capacity to obliterate itself, and to conserve the trace of this same obliteration eternally, maintained as an absolute sign of the irreducibility of the signified’s desire. This it is the witness of the capacity of the signifier to maintain itself beyond life, as the fundamental articulation of a pure desire of all positive determination. If it is true that the signifier exceeds the signifying sphere that remains powerless to represent the Real, it is precisely in reason of the fact that the signifier disposes of this capacity to obliterate itself and to preserve its state as eternal witness, the movement by which it obliterates itself, by which it rejects the possibility of confounding itself with life. But life, because it is guided by the principle of pleasure and satisfaction it receives from it, is inevitably headed towards death.

In obliterating itself, the signifier holds onto the Subject, the hard kernel of its being as pure desire. It is the passage from a state of a still-incomplete signifier to a second power that incarnates the passage from the first death to the second death. This is why Antigone rebels against Creon, because he condemned the corpse of her brother Polynices to remain outside its sepulchre. As a trace of the life now extinguished, it does not conform to its signifier, that is, to Polynices as Empty Subject of the Thing.

2. The Real of the Subject and the Graph of Desire.

The subjective dependence on the desire of the Other stems from what Lacan, in Le désir et son interpretation, called the “principle of commutativity”. This principle describes the fundamental liaison of the child with his Mother from his first demands on her as a support of symbolic interaction. She is capable of receiving the need that the child addresses to her only in so far as she interprets it, that is, converts injuthe child’s corporal manifestation, or babble, into meaningful requests. This conversion determines the subject’s entry into the symbolic universe.

Hence, this is why Lacan argues that one always receives one’s own message from the Other, as the big Other is both upstream and downstream of meaning: for the child’s need to make sense, he must first alienate himself from the field of what makes sense for the Other, he must align himself with the Other’s desire, in order to then signify him his need, relative to what the Other may understand of it. Hence, the route of the signification remains circular; the Other merely sends the ball back to himself, since it is from his desire to understand one expression over another, to interpret in one way more than another, with all the arbitrariness that such a choice imposes on the subject of his demand, that a significant expression (gesticulation, cry, babble) becomes symbolic. It is on this occasion that the universe of signification emerges.

This is why psychoanalysis does not stop at the description of the conventions already ready to be established; it locates the origin of such a dependence of the subject vis-ˆ-vis the conventions beginning with the first relations of the subject with his mother, as a support of the code, as the first encounter of the subject with the big Other. This genesis of meaning, under the motif of the alienation of the subject in a desire that he encounters, that he transcends and upon which he depends in order to acquire meaning, is the very enigma of psychoanalysis, the fundamental trauma upon which the subject’s iapparatus rests.

Psychoanalysis does not content itself with understanding the relationships of the subject to conventions for themselves, it investigates their genesis, in linking the question of conventions to the description of the traumatic experience that constitutes the subject’s enigmatic encounter with the desire of the Other. It is this circular desire that sets the subject up as a container (through harnessing his pre-symbolic performances in the filaments of the symbolic demand) of a particular signifying value with regard to an already-constituted desire. In such a case, it is legitimate to ask whether (just as in Austin), this non-linguistic utterance is preserved after the subject’s entry into the language of the Other.

In reality, yes, but in a mode that is very distinct from the way Austin breaks down the speech act into illocutionary and perlocutionary. What remains of the process of conversion of the pre-symbolic manifestations of the child in the symbolic sphere is the object a, presented by Lacan as the detritus of the operation of symbolic transformation accomplished by the subject’s entry into the field of recognition by the big Other of the symbolic value of his primordial performances. The question is, therefore, that of knowing how, starting from the Graph of Desire, one may restore all its weight to the real enunciative efficiency, such as it is always played out beyond all symbolisation, as a call or cry to the Other.

How to regain, within the symbolic field, the Real in which the language act roots itself if, to follow the Lacanian definition of the Real, the Real belongs to the order of that which escapes the symbolic, of that which presents itself to the symbolic as impossible? The first important conclusion is that the apparatus that Searle developed in Speech Acts [30] is in every point identical to the description of the first stage of the Graph of Desire.

Indeed Searle’s ‘principle of expressibility’ postulates the existence of an analytical conjunction of mental intentions to language conventions. There is no intention that is not found to express itself in a typically conventional procedure, and this is true a priori for Searle. For Searle, each conventional procedure corresponds to an intentional pragmatic value. It is without doubt the reason why Searle remains so insensitive to perlocutionary phenomena; it is that, for him, the conventional field absorbs the entire sphere of expressivity of the subject (reduced to the intentional subject).

In this way, the procedure described by Lacan at the first stage of the Graph of Desire corresponds rather impressively to the system described by Searle in Speech Acts. Lacan’s theory would have been identical to that of Searle if Lacan had not distinguished the enunciation from the utterance in showing that the utterance belongs to the sphere of intentional discourse and the field of the desiring subjectivity is never reducible to that which reflects the intentional discourse. Lacanian subjectivity is not only made of intentions that branch onto conventions under the benevolent validation of the big Other. Because – and it is that which the Graph of Desire demonstrates – the intentional field of the subject remains a retroactive reconstruction after the fact, produced by the big Other. It is there that all the subversion of the Lacanian apparatus resides.

The pragmatic (in Searle, at least) presents things in the following way: there is an intention which, in order to express itself, uses a conventional procedure which is specific to it. Searle’s method is the following:

S utters sentence T and means it (means literally what he says) =

S utters sentence T and

(a) S intends (i-i) the utterance U of T to produce in H the knowledge (recognition, awareness) that the states of affairs specified by (certain of) the rules of T obtain. (Call this effect the illocutionary effect, IE)

(b) S intends U to produce IE by means of the recognition of i-i

(c) S intends that i-I will be recognized in virtue of (by means of) H’s knowledge of (certain of) rules governing (the elements of) T [31]

Intention never precedes the convention that expresses it; only once the field of the signifier is pinned down (by capitonnage) by the big Other, can one infer from an often-used conventional procedure that the speaker wanted to say something. Under the effect of capitonnage by the code (vector D’), the subject introduces his linguistic performance as being carried by an intentional agent/speaker. However, this agent/speaker only appears after the fact, once the big Other has fixed and recognized the signification of a performance, and it is by virtue of this recognition that is identified the intentional identity of the subject that was its bearer.

At the level of the code: the subject is recognized as intentional agent, but this identity did not precede the fixation of sense by the big Other of a signifying sequence mobilized by the subject to an infra-symbolic level. This is why, exactly as in Searle, Lacan’s intentions are soldered to conventions: no intention can be expressed outside a codified procedure (recognized by the big Other). From Lacan’s point of view, Searle’s naiveté was to infer (from usage conforming to the code) the existence of an intentional sphere upstream from its linguistic expression.

For Lacan, the procedure is exactly the inverse: it is the linguistic expression that precedes the discursive intentions and that results retroactively from the value of the expression authenticated by the big Other. However, it is the operation of conversion of a need deprived of meaning and of signifiers that he mobilized with the intention of making himself understood by the big Other; it is thus the conversion of the real need into symbolic demand, a tributary of the interpretative intervention of the Other, which is obliterated precisely at the level of the signified signification obtained in s(A). On the part of the signified, we find a signification referring back to the existence of a subject speaker conscious of himself – that which Lacan calls the semblance of subject, the Imaginary ego – situated upstream of the language and utilising it in order to transmit (under the form of pragmatic contents) its volitional states. The illusion of the signified is not uniquely an illusion as to meaning, but equally an illusion in that it truncates the operation from which the signification springs up.

The Graph of Desire shows that need does not become a demand until after the fact. The need as it exists does not carry any request before the Other has taken it in charge. This emergence of the signification after the act is a constant in Lacan’s teaching: it is only once the interpretation of the Other is realized that the life of the subject can be understood from the perspective of a truth through which this experience of life will appear as endowed with meaning. The interpretation by the Other realizes the truth in a performative manner; it is not discovered in the speech of the patient; it constitutes it. Meaning never precedes the act of interpretation upon which it depends. As Lacan affirms in Seminar XVIII.

(Interpretation) is true only by what comes afterwards, just like an oracle. Interpretation is not put to a truth test that slices it up, yes or no; it triggers the truth as it is. It is true only to the extent to which it is followed up. [32]

On the Graph of Desire, need belongs to the sphere of the Real (vector delta/A), just as its primordial bodily displays/demonstrations (the chain of signifiers vector D/A/S) before the interpretative intervention of the big Other) which, as they exist, have no signification. It is at the moment of the encounter with the Other as interpreting, that the subject of the real from where it is found, is transformed into an intentional imaginary subject at the first level of the graph, then, at the second level, as subject of an unconscious demand.

It is at that moment that his need suffers from the interpretation by the big Other, and finds itself reconstructed under the effect of this interpretation, as the expression of an intention.

Otherwise said, in the haste signified by the signifying chain at the first stage of the graph, the Real of the act does not reside in the usage that an intentional subject makes of a conventional procedure. Rather, the Real of the act finds itself in the impossible translation of his need by the big Other, and of the expressions located first in the element of non-sense, of the signifying register, before its symbolic interpretation by the big Other.