1. The principle of the insufficient ground

Love lets us view imperfections as tolerable, if not ador�able. But it’s a choice. We can bristle at quirks, or we can cherish them. A friend who married a hot-shot lawyer remembers, “On the first date, I learned that he could ride out rough hours and stiff client demands. On the second, I learned that what he couldn’t ride was a bicycle. That’s when I decided to give him a chance.”

The lesson of the so-called “endearing foibles,” referred to in this quote from Reader’s Digest is that a choice is an act which “ret�ro�ac�tive�ly grounds its own reasons.” Between the causal chain of reasons provided by knowledge (S2 in Lacanian mathemes) and the act of choice, the decision which, by way of its un�con�di�tion�al character, concludes the chain (S1), there is always a gap, a leap which cannot be accounted for by the preceding chain.1 Recall what is perhaps the most sublime moment in a melodrama: a plot�ter or a well-meaning friend tries to convince the hero to leave (the sex�u�al partner, leader) by way of enumerating the latter’s weak points. Yet, un�know�ing�ly, he there�by provides reasons for con�tin�ued loyalty; his very coun�ter�ar�gu�ments function as arguments: “for that very reason s/he needs me even more.”2 This gap between reasons and their ef�fect is the foundation of trans�fer�ence, the transferential relation epit�o�mized by love. Even our sense of common de�cen�cy finds it repulsive to list the reasons for which one loves somebody. The moment one can say, “I love this individual for the following reasons…” it is clear that this is not love proper.3 In the case of true love, apropos of some feature which is in itself negative, which offers opposition, one may say “For this very reason I love this person even more!” Le trait unaire, which triggers love, is always such an index of an im�per�fec�tion.

This circle which determines the subject but only through those rea�sons which one recognizes retroactively as such, is what Hegel has in mind with the “positing of presuppositions.” The same logic is at work in Kant’s philosophy. The Anglo-Saxon literature on Kant refers to the “In�cor�po�ra�tion Thesis:”4 there is always an element of au�ton�o�mous “spontaneity” pertaining to the subject, making it ir�re�duc�ible to a link in the causal chain. True, one can conceive of the subject as submitted to the chain of causes, which determine conduct in ac�cor�dance with “pathological” interests; therein con�sists the wa�ger of utilitarianism. Since the sub�ject’s conduct is wholly de�ter�mined by seeking the maximum of pleasure and the min�i�mum of pain, it would be possible to govern one, and to predict the steps, by controlling the external con�di�tions which influence de�ci�sions. What eludes utilitarianism is the very el�e�ment of “spontaneity” in German Idealism’s sense—the very opposite of its everyday mean�ing: surrendering oneself to the immediacy of emo�tion�al impulses, for example. Ac�cord�ing to German Idealism, when one acts “spon�ta�ne�ous�ly” one is not free, but a prisoner of one’s immediate nature, de�ter�mined by the causal link which chains one to the external world. On the contrary, true spontaneity is char�ac�ter�ized by the moment of re�flex�iv�i�ty; reasons count only insofar as I “incorporate” them, “accept them as mine.” In other words de�ter�mi�na�tion of the subject by the other is always self-de�ter�mi�na�tion. Thus decision is si�mul�ta�neous�ly dependent on and in�de�pen�dent from its con�di�tions. In this sense the subject in German Idealism is always one of self-con�scious�ness. Therefore any im�me�di�ate ref�er�ence to my nature “What can I do? I was made like this” is false. The relation to my impulses is always mediated; they de�ter�mine me insofar as I rec�og�nize them, and that’s why I am fully responsible for them.5

Another instance of “positing the presuppositions” is the spon�ta�ne�ous ideo�log�i�cal narration of ex�pe�ri�ence and activity. What�ev�er one does, one always situates the action within a symbolic context, charged with conferring meaning. In the former Yu�go�sla�via, a Serbian fight�ing the Albanian Muslims and the Bosnians con�ceives of the civil war as the last act in the century’s on-going defense of Chris�tian Europe against Turkish infiltration. Bolsheviks con�ceived of the October Rev�o�lu�tion as the con�tin�u�a�tion and suc�cess�ful conclusion of previous radical pop�u�lar uprisings: from Spartacus in ancient Rome to Jacobins during the French Rev�o�lu�tion. This narration is assumed tacitly even by some critics who, for example, speak of Stalinist Thermidor. Khmer Rouge in Cambodia or Sendero Luminoso in Peru understand their move�ment as a return to the glory of an an�cient empire. The Hegelian point here is that this narration is a retroactive reconstruction for which one is re�spon�si�ble—never a given fact. One can never refer to it as a founding con�di�tion, the context or pre�sup�po�si�tion of activity. As pre�sup�po�si�tion it is always already “posited.” Tradition is tradition insofar as it gets constituted as such.

In his critical remarks on German Idealism, Lacan equates self-consciousness with self-transparency, dismissing it as the most bla�tant case of philosophical illusion, which consists in denying the subject’s constitutive decentrality. However, self-consciousness in German idealism not only has nothing to do with any kind of transparent self-identity of the subject, it is rather another name for what Lacan has in mind when he points out that every desire is the “desire of a desire.” The subject never finds a mul�ti�tude of desires, only entertains towards them a reflected relationship. By way of actual desiring, one implicitly answers the question—which of your desires do you desire, have you chosen one? Concerning Kant, self-con�scious�ness, thus con�ceived, is pos�i�tive�ly founded on the non-trans�par�en�cy of the subject to itself: the Kantian transcendental ap�per�cep�tion (the self-con�scious�ness of pure I) is possible insofar as I am unattainable to my�self in my noumenal dimension, as “Thing which thinks.”6 There is, of course, a point at which this circular “positing of the presuppositions” reaches a deadlock; the key to this deadlock is provided by the Lacanian logic of non-all—pas-tout.7 Al�though “nothing is pre�sup�posed which was not pre�vi�ous�ly pos�it�ed,” every “particular” pre�sup�po�si�tion can be dem�on�strat�ed to be posited, not natural but nat�u�ral�ized—it would be wrong to draw the seemingly obvious “uni�ver�sal” con�clu�sion that “ev�ery�thing pre�sup�posed is posited.” The pre�sup�posed X, “nothing in par�tic�u�lar,” totally substanceless, nev�er�the�less resists being ret�ro�ac�tive�ly “pos�it�ed.” Lacan calls this X the real, the un�at�tain�able, elusive je ne sais quoi.

In Gender Trouble, Judith Butler8 demonstrates how the difference of sex and gender is the difference be�tween a biological fact and a cultural/symbolic formation which, a decade ago, was widely used by feminists in order to show that “anatomy is not destiny.” Woman as a cultural product, already posited, is not de�ter�mined by her biological status, can never be un�am�big�u�ous�ly fixed, pre�sup�posed as a pos�i�tive fact. The way one draws the line separating culture from nature is determined by a specific context. This cultural overdetermination of de�mar�ca�tion between gender/sex, however, should not precipitate one into ac�cept�ing the Foucauldian notion of sex as the effect of “sexuality,” an het�er�o�ge�neous tex�ture of discursive practices. What gets lost there�by is the dead�lock of the real. Thus arises the thin yet crucial line separating Lacan from the deconstructionists, from the opposition between nature/culture, which is cul�tur�al�ly overdetermined—there is no par�tic�u�lar element one can isolate as “pure nature.” One should not draw the con�clu�sion that everything is culture. Nature as real remains the unfathomable X resisting cultural “gentrification.” Or, in another way: the Lacanian real is the gap separating the Particular from the Universal. It prevents one from accomplishing the ges�ture of universalization and jumps from the premise that every par�tic�u�lar element is P, to the con�clu�sion that all elements are P.

Consequently, there is no logic of prohibition in�volved in the notion of the real as impossible, non-symbolizable. In Lacan the real is not sur�rep�ti�tious�ly consecrated, organized as the domain of the inviolable. When Lacan defines the “rock of castration” as real, this in no way implies that castration is excepted from the discursive field as a kind of untouchable sacrifice. Every demarcation between the symbolic and the real, every ex�clu�sion of the real as prohibited/inviolable, is a symbolic act par excellence. Such an inversion of impossibility into prohibition/exclusion occults the inherent dead�lock of the real. In other words, Lacan’s strategy is to prevent any tabooing of the real. One can “touch the real” only by applying oneself to its symbolization, up to the very failure of this endeavor. In Kant’s Critique of Pure Rea�son, the only proof that there are things beyond phenomena are paralogisms, inconsistencies in which rea�son gets entangled the moment it ex�tends the application of cat�e�go�ries beyond the limits of experience. In the same way in Lacan on touche le réel—one touches the real of jouissance by the impasses of formalization.9 In short the status of the real is thor�ough�ly non-substantial; it is a product of failed attempts to integrate into the symbolic.

The impasse of “presupposing,” of listing the pre�sup�po�si�tions, the chain of ex�ter�nal causes/conditions of some pos�it�ed entity, is the reverse of these “troubles with the non-all.” An entity can easily be reduced to the totality of its presuppositions. What is missing from the se�ries of pre�sup�po�si�tions, however, is the performative act of formal conversion which ret�ro�ac�tive�ly posits these pre�sup�po�si�tions, and makes them into what they are: the pre�sup�po�si�tions of… (like the above mentioned example of the act which retroactively posits its reasons). This “dot�ting of the i” is the tautological gesture of the Master Signifier constituting the entity as One. Thus looms asymmetry: the positing of pre�sup�po�si�tions chanc�es upon its limit in the “feminine” non-all. What it eludes is the real, whereas the enumeration of the pre�sup�po�si�tions of the posited content made into a closed series through the “masculine” performative.

Hegel tries to resolve this impasse of “positing reflection” and “external reflection” in his Logic of Essence—the second part of his Science of Logic. The aim of the following examination is to discover in Hegel’s solution the same pattern of an elementary ideo�log�i�cal operation.

2. Ground versus conditions

The fundamental antagonism of Hegel’s Logic of Essence is the an�tag�o�nism between “ground” and “conditions,” between the inner essence, the “true nature” of a thing, and the external circumstances which render possible the realization of this essence, i.e., the impossibility to reach a common measure between these two di�men�sions, to co�or�di�nate them in a “higher-order synthesis.” Only in the third part of Logic, the “subjective logic” of Notion, this in�com�men�su�ra�bil�i�ty appears surpassed. Therein consists the alternative be�tween “pos�it�ing” and “external” reflection: do people create the world they live in from within themselves, au�ton�o�mous�ly, or does their activity result from external cir�cum�stanc�es? Philosophical common sense would im�pose here the compromise of a “proper measure.” True, one has the pos�si�bil�i�ty of choice, or one can realize our freely conceived projects. But the framework of tradition, of inherited cir�cum�stanc�es delineates our field of choices… or, as Marx put it in his Eigh�teenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte:

Men make their own history; but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under cir�cum�stanc�es chosen by them�selves, but under cir�cum�stanc�es directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.

However, it is precisely such a “dialectical synthesis” that Hegel declines. There is no way to draw a line separating the two aspects: every inner potential can be translated—its form can be converted—into an external condition, and vice versa. In short what Hegel does here is very precise: undermining the usual notion of the relation between the inner potentials of a thing and the external con�di�tions which render (im)possible the realization of these po�ten�tials, “he posits between these two sides the sign of equality.” The con�se�quenc�es of this are far more rad�i�cal than they may seem; they concern above all the radically anti-evolutionary character of Hegel’s philosophy. To ascertain it, one has only to recall the notional couple “in itself/for itself.” This couple is usually taken as the supreme proof of Hegel’s trust in evolutionary progress—the de�vel�op�ment from “in-itself” into “for-itself,”—yet it suffices to look closely at it in order to dispel this phantom of Evolution. The “in-itself” in its opposition to “for-itself” means at one and the same time

—what exists only potentially, as an inner pos�si�bil�i�ty, con�trary to the actuality wherein a pos�si�bil�i�ty has externalized and realized itself; and

—actuality itself in the sense of external, im�me�di�ate, “raw” objectivity, which is still opposed to subjective mediation, which is not yet internalized, rendered conscious; in this sense, the “in-itself” is actuality in so far as it has not yet reached its concept.

The simultaneous reading of these two aspects undermines the usual idea of dialectical progress, a gradual re�al�iza�tion of the object’s inner potentials as spontaneous self-de�vel�op�ment. Hegel is quite outspoken and explicit: the inner potentials of the self-de�vel�op�ment of an object and the pressure exerted on it by an ex�ter�nal force “are strictly correlative.” They form two sides of the same conjunction. In other words, the po�ten�ti�al�i�ty of the object must in turn be present in its external actuality, under the form of het�er�on�o�mous coercion. To use Hegel’s example, to say that a pupil at the beginning of his education po�ten�tial�ly knows, that in the course of development he will realize creative potentials, equals saying that such inner po�ten�tials must be present from the very beginning in external actuality. Likewise, the authority of the Master exerts pres�sure upon his pupil. Nowadays one can add the sadly famous case of the working-class as revolutionary subject. To affirm that the work�ing class is “in itself” a rev�o�lu�tion�ary subject, is to assert that this po�ten�ti�al�i�ty must already have been actualized in the Party which knows its mission in advance, and there�fore exerts pres�sure upon the working class, guiding it towards realization. In this way, the “leading role” of the Party is le�git�i�mized—its right to “educate” the working class in accordance with its potentials, to “convey” it into its historical mission.

One can see, thus, why Hegel is as far as pos�si�ble from the evolutionist’s notion of the pro�gres�sive development of “In-itself” into “For-itself.” The category of “in itself” is strictly correlative to “for us”—for some consciousness external to the thing-in-itself. To say that a lump of clay is “in itself” a pot, equals saying that this pot is already present in the mind of the craftsman who will impose the form of pot onto the clay. The current way of saying “under the right conditions the pupil will realize his potentials,” is thus de�cep�tive: when, in excuse of his “failure” to realize his po�ten�tials, one insists that “he would have realized them, if only the conditions had been right”—one approaches cynicism akin to Brecht’s famous state�ment from his Beggar’s Opera “We would be good instead of being so rude, if only the cir�cum�stanc�es were not of this kind!”

For Hegel external cir�cum�stanc�es are not an impediment to the re�al�iza�tion of inner potentials, but on the contrary “the very arena in which the true nature of these inner potentials is to be tested.” Are they true potentials or just vain illusions about what might have happened? Or, to put it in Spinozian terms, “positing reflection,” observes things as they are in their eternal es�sence, sub specie aeternitatis, whereas “external reflection” observes them sub specie durationis, in their dependence on a series of contingent ex�ter�nal circumstances. Here, everything hinges on “how” does Hegel over�come “external reflection.” If his aim were simply to reduce the externality of con�tin�gent conditions to the self-mediation of the inner essence-ground—the usual notion of Hegel’s idealism—then Hegel’s phi�los�o�phy would truly be a mere “dynamized Spinozism.” What does Hegel actually do?

Recall the usual mode of explaining the outbursts of racism which makes use of the categorial couple of ground and conditions/circumstances: one conceives racism—the so-called outbursts of irrational mass sadism—as a latent psychic disposition, a kind of Jungian archetype, which comes forth under cer�tain conditions like social instability and crisis. Within this lense the racist disposition is the “ground,” and current political struggles the “circumstances,” the conditions of its ef�fec�tu�a�tion. However, what counts as ground and what counts as conditions is ultimately contingent and ex�change�able. Therefore one can easily accomplish the Marxist re�ver�sal of the above men�tioned psy�chol�o�gist’s perspective, and con�ceive the present po�lit�i�cal struggle as the only true de�ter�min�ing ground.

In the present civil war in ex-Yugoslavia, the “ground” of the Serbian aggressivity is not to be sought in any primitive Balkan warrior archetype, but within the struggle for power in post-Com�mu�nist Serbia (the survival of the old Com�mu�nist state ap�pa�ra�tus)—the status of eventual Serbian bellicose dispositions and other similar archetypes (the “Croatian genocidal character,” the “cen�ten�ni�al tradition of ethnic hatreds in Balkan countries”) is precisely that of the conditions/cir�cum�stanc�es in which the power struggle re�al�iz�es it�self. The “bellicose dispositions” are precisely latent conditions which are actualized, drawn from their shadowy half-ex�ist�ence, by the recent political strug�gle as their de�ter�min�ing ground. One is thus fully justified in saying that “what is at stake in the Yugoslavian civil war are not archaic ethnic conflicts: these centennial hatreds are in�flamed only on account of their function in the recent political strug�gle.”10

How, then, can one avoid this mess, this ex�change�abil�i�ty of ground and circumstances? Consider another example: the re�nais�sance is re�dis�cov�ery (rebirth) of antiquity which exerted a crucial influence on the XVth century’s break with the mediaeval way of life. The first ob�vi�ous explanation of that impact is that the newly discovered antique tradition brought about a dissolution of the mediaeval “paradigm”—here, however, a ques�tion pops up: why did antiquity begin to exert its influence at this very moment? A possible answer is: due to the dis�so�lu�tion of mediaeval social links, a new zeitgeist emerged which made for the response to antiquity.

Something must have changed so that people became able to perceive an�tiq�ui�ty not as the pagan kingdom of sin but as the model to follow.

That is all very well, but one remains locked inside the vicious circle. This new zeitgeist took shape through the dis�cov�ery of antique texts. In a way ev�ery�thing was already there, in the external circumstances; the new zeitgeist formed through the in�flu�ence of antiquity enabling renaissance thought to shatter the me�di�ae�val chains. Yet for this to take place, the new zeitgeist should already have been active. The only way out of this impasse is therefore the intervention at a certain point, of a tau�to�log�i�cal gesture; the new zeitgeist had to constitute itself by literally “pre�sup�pos�ing itself in its exteriority.” In other words it was not sufficient for the new zeit�geist to posit retroactively these external conditions (the antique tra�di�tion) as “its own.” It had to (presup)pose itself as already present in them. The return to ex�ter�nal conditions (to an�tiq�ui�ty) had to co�in�cide with the return to the foundation, to the “thing itself,” to the ground. The “renaissance” conceived of itself as the return to the Greek and Roman foun�da�tions of Western civ�i�li�za�tion. There is thus no inner ground where actualization de�pends on external circumstances. The external relation of pre�sup�pos�ing (ground pre�sup�pos�es conditions and vice versa) is surpassed in a pure tau�to�log�i�cal gesture, by means of which the thing “pre�sup�pos�es itself.” This tau�to�log�i�cal gesture is “empty” in the sense that it does not contribute anything new; it only ret�ro�ac�tive�ly ascertains that

the thing in question “is already present in its conditions.” The to�tal�i�ty of these conditions “is” the actuality of the thing. Such an empty gesture provides the most elementary definition of a “symbolic” act.

Thus one arrives at the fundamental paradox of “re�dis�cov�er�ing tra�di�tion” at work in the con�sti�tu�tion of national identity; a nation finds its sense of self-identity through such a tau�to�log�i�cal gesture, by way of discovering itself as already present in its tradition. Con�se�quent�ly, the mech�a�nism of the “rediscovery of national tradition” cannot be reduced to the “positing of presuppositions,” in the sense of the retroactive positing of conditions as “ours.” Rather, the point is in the very act of returning to its external conditions, “the national thing returns to itself.” The return to conditions is ex�pe�ri�enced as the “return to one’s true roots.”

3. The tautological “return of the thing to itself”

Although “existing socialism” has already receded into a distance conferring upon it the nostalgic magic of a post-modern lost object, one may still recall a well-known joke on what so�cial�ism is. A social system dialectically synthesizes its entire previous history: from the prehistoric classless society it took primitivism, from antiquity slave labor, from medieval feu�dal�ism ruthless dom�i�na�tion, from cap�i�tal�ism exploitation “and from so�cial�ism a name.” The Hegelian tau�to�log�i�cal gesture of the “return of the thing to itself” includes in the definition of the object its name. That is, after decomposing an object, one looks in vain for some specific feature holding to�geth�er these parts and makes of them a unique, self-identical thing. As to its properties and in�gre�di�ents, a thing is wholly “outside itself,” in its external conditions. Every positive feature is already present in the circumstances which are not yet this thing. The sup�ple�men�ta�ry op�er�a�tion which makes from this bundle a unique, self-identical thing is the purely symbolic, tau�to�log�i�cal gesture of pos�it�ing these ex�ter�nal conditions as the conditions/components of the thing, while simultaneously pre�sup�pos�ing the existence of ground which holds to�geth�er the multitude of con�di�tions.

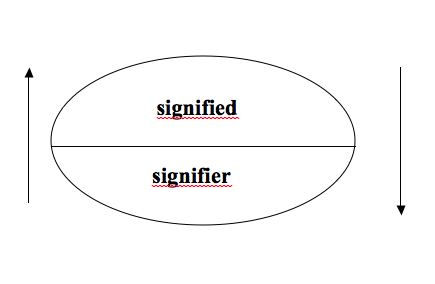

To throw our Lacanian cards on the table, this tau�to�log�i�cal “return of the thing to itself” rendering the concrete structure of self-identity Lacan designates as the point de capiton, at which the signifier falls into the signified (as in the above joke on socialism, where the name functions as part of the designated thing). Recall an example from popular culture: the killer shark in Spielberg’s Jaws.11 It is wrong and mis�lead�ing to search directly for its ideological meaning. Does it symbolize the threat of the Third World to America epit�o�mized by the archetypal small town? Is it the symbol of the ex�ploit�ative nature of capitalism itself (Fidel Castro’s in�ter�pre�ta�tion)? Does it stand for the untamed nature which threatens to disrupt the routine of our daily lives? In order to avoid this lure, one should shift perspective: the daily life of common man is dominated by an inconsistent multitude of fears (he can become the victim of big business manipulations; Third World im�mi�grants seem to intrude into his small orderly uni�verse; unruly nature can destroy his home…), and the ac�com�plish�ment of Jaws consists in an act of purely formal conversion, providing a common “container” for these free-floating, in�con�sis�tent fears by anchoring them, “reifying” them in the figure of the shark. Consequently, the function of the fas�ci�nat�ing presence of the shark is precisely to block any further inquiry into the social meaning (social mediation) of the phenomena which arouse fear in common man. To say that the murderous shark symbolizes the above men�tioned series of fears is to say too much and not enough at the same time. It does not symbolize them, since it literally annuls them by occupying the place of the object of fear. It is therefore more than a symbol: the feared “thing itself.” On the other hand, it is also less than a symbol, since it does not point towards the symbolized content, but rather blocks access to it, renders it invisible.

Moreover, the shark is homologous with the anti-Semitic figure of the Jew: “Jew” is the answer, the explanation offered by anti-Semitism, to the multitude of fears experienced by “common man” in an epoch of social dissolution (inflation, un�em�ploy�ment, cor�rup�tion, moral degradation). Behind all these phe�nom�e�na there is the in�vis�i�ble hand of the “Jewish plot.” Again, the cru�cial point, is that the designation “Jew” adds no new content: the entire content is already present in the external con�di�tions (cri�sis, moral de�gen�er�a�tion…). The name “Jew” is only the supplementary feature ac�com�plish�ing a kind of transubstantiation and changing all these el�e�ments into many man�i�fes�ta�tions of the same “ground,” the “Jewish plot.” Para�phras�ing the joke on socialism, one could say that anti-Semitism takes from the economy un�em�ploy�ment and in�fla�tion, from politics parliamentary corruption and in�trigue, from morality degeneration, from art “incomprehensible” avant-gardism, “and from the Jew its name.” This name enables one to recognize be�hind the multitude of external con�di�tions the ac�tiv�i�ty of the same ground….

Therein consists another dialectic of con�tin�gen�cy and ne�ces�si�ty: as to their content, they fully coincide (in both cases, the only positive content is the series of conditions which form part of actual life-experience: economic crisis, political chaos, the dis�so�lu�tion of ethical links…). The pas�sage of con�tin�gen�cy into necessity is an act of purely formal conversion, the gesture of adding a “name” which confers upon the contingent series the mark of necessity, thereby transforming it into the expression of some hidden ground, the “Jewish plot.” So the “performativity” at work in this act of formal conversion in no way designates the pow�er of freely “creating” the designated content—words mean what we want them to mean. “Quilting” only structures the found material, ex�ter�nal�ly imposed. The act of naming is “performative” only and precisely insofar as “it is always-already part of the definition of the sig�ni�fied content.”12

Hegel resolves the deadlock of positing and external re�flec�tion (the vicious circle of positing the pre�sup�po�si�tions and of enu�mer�at�ing the presuppositions of the posited content) by means of the tautological return-upon-itself of the thing, in its very external presuppositions. The same tau�to�log�i�cal gesture is already at work in Kant’s analytic of pure reason: the synthesis of the multitude of sensations in the rep�re�sen�ta�tion of the object which belongs to “reality” implies an empty surplus. The positing of an X is the un�known sub�stra�tum of the perceived phenomenal sensations. Suf�fice it to quote Findlay’s precise formulation:

…we always refer appearances to a Tran�scen�den�tal Object, an X, of which we, however, know noth�ing, but which is non-the-less the objective cor�re�late of the synthetic acts inseparable from think�ing self-con�scious�ness. The Transcendental Object, thus con�ceived, can be called a Noumenon or thing of thought (Gedankending). But the reference to such a thing of thought does not, strictly speaking, use the categories, but is something like “an empty synthetic gesture” in which nothing objective is really put before us.13

The transcendental object is thus the very op�po�site of the Ding-an-sich: that is, empty insofar as it is devoid of any objective content. To obtain its notion, one has to abstract from the sensible object its entire sensible content, all sen�sa�tions by means of which the subject is af�fect�ed by Ding. The empty X which remains is “the pure objective correlate/effect of the subject’s autonomous/spontaneous synthetic activity.” To put it in a par�a�dox�i�cal way: the transcendental object is the “in-itself” insofar as it is for the sub�ject, posited by it, pure “positedness” of an in�de�ter�mi�nate X. This “empty synthetic gesture” adding nothing positive to the thing, and yet, in its very capacity of an empty gesture, constitutes it, makes it into an object, is the act of sym�bol�iza�tion in its most el�e�men�ta�ry form. Findlay points out that the tran�scen�den�tal object:

is not for Kant different from the object or objects which appear to the senses and which we can judge about and know… but it is the “same” object or objects conceived in respect of certain intrinsically inapparent features, and which is in such re�spects incapable of being judged about or known.14

This X, this irrepresentable surplus which adds itself to the series of sensible features, is precisely the “thing-of-thought”/Gedankending: it bears witness to the fact that the object’s unity does not reside in it, but is the result of the subject’s syn�thet�ic activity—as with Hegel, where the act of formal con�ver�sion inverts the chain of conditions into the unconditional Thing, founded in itself.

Let’s briefly return to anti-Semitism, to the “synthetic act of ap�per�cep�tion” which, out of the mul�ti�tude of imagined features of Jews, constructs the anti-Semitic figure of “Jew.” To pass for a true anti-Semite, it is not enough to claim that one opposes Jews because they are exploitative, greedy in�trigu�ers, nor is it sufficient for the signifier “Jew” to designate this series of positive features. One must accomplish the crucial step further by saying “they are like that: exploitative, greedy…, because they are Jews.” The “transcendental object” of Jewishness is pre�cise�ly that elusive X which makes a Jew into a “Jew” and for which one looks in vain among the positive prop�er�ties. This act of pure formal conversion, the “synthetic act” of uniting the series of positive features in the signifier “Jew” and thereby trans�form�ing them into so many manifestations of the “Jewishness” as their hidden ground, “brings about the ap�pear�ance of an objectal surplus,” of a mysterious X which is “in Jew more than Jew;” in other words: of the transcendental object.15

1. Of course there are good reasons to believe in Jesus Christ, “but these reasons are fully com�pre�hen�si�ble only to those who already believe in Him.”

2. The same for Ronald Reagan: the more journalists enumerated his slips of tongue and other faux pas, the more they strengthened his popularity. As to Reagan’s “teflon presidency,” see Joan Copjec, “The unvermögender Oth�er…” in New Formations 14, London: Routledge, 1991. On another level the gap sep�a�rat�ing S1 from S2, the act of decision from the chain of knowl�edge, is provided by the institution of jury in justice: the jury ac�com�plish�es the act of decision, a verdict of “guilt” or “innocence,” and it’s up to the judge to ground it in knowledge, translate it into pun�ish�ment. Why can’t the judge himself pass the verdict? For Hegel, jury embodies the principle of free subjectivity: the crucial fact is that it’s composed of a group of peers of the accused selected by lottery—they stand for “anybody.” I can be judged only by my equals, not by a superior agency speaking in the name of some inaccessible Knowledge. Jury implies an aspect of contingency, suspending the principle of sufficient ground. By entrusting the jury with passing the verdict, the moment of uncertainty is preserved. Until the end one cannot be sure what will be; the judgement’s actual pro�nun�ci�a�tion is always a sur�prise.

3. The paradox is that there is “nothing” behind the series of positive, observable features: the status of that mysterious je ne sais quoi which makes me fall in love is ultimately that of a pure semblance. One can see how a “sincere” feeling is necessarily based upon illusion—I am “really,” “sincerely,” in love, only insofar as I believe in your secret agalma.

4. As for this “Incorporation Thesis,” cf., Henry E. Allison’s Kant’s Theory of Freedom, Cam�bridge: Cambridge Uni�ver�si�ty Press, 1990.

�

5. The adverse procedure is also false: the attribution of personal responsibility and guilt which relieves one of probing into the con�crete circumstances. The moral-majority practice of the ethical qual�i�fi�ca�tion of the higher crime rate among African Americans—criminal dis�po�si�tions, moral insensitivity…—

precludes the analysis of their social, eco�nom�ic and political con�di�tions.

6. The ultimate proof of how this reflectiveness of desire that constitutes “self-consciousness” has nothing to do with the subject’s self-transparency. The very opposite, it involves the subject’s radical splitting in the par�a�dox�es of love-hate. Hollywood de�scribed Erich von Stroheim who, in the 30s and 40s, regularly played sadistic German officers, as “a man you’ll love to hate:” to “love to hate” means that this somebody fits perfectly the scape�goat-role of attracting hatred. At the opposite end, the femme fatale in the noir universe is clearly a woman one “hates to love:” we know she means evil, so it’s against our will that we are forced to love her, and we hate our�selves and her for it. Tautological cases of this reflectivity of love-hate are no less paradoxical. Saying I “hate to hate you,” points towards a splitting: I really love you, but for certain reasons I am forced to hate you, and I hate myself for it.

7. As to this logic of the “non-all,” cf. Jacques Lacan, Le seminaire, livre XX: Encore, Paris: Editions du Seuil 1975; two key chapters are translated in Feminine Sexuality, New York: W.W. Norton, 1982.

8. Cf. Judith Butler, Gender Trouble, New York: Routledge, 1990.

9. Lacan’s statement that “there is no sexual relation” does not contain a hidden normativity. His point is “it is not possible to formulate any norm which should guide one with a legitimate claim to universal validity:” every attempt to formulate such a norm is a sec�ond�ary endeavor to mend an “original” impasse. Lacan avoids the trap of the cruel superego: the subject cannot meet its demands, thereby branding its very being with a constitutive guilt. The relation of the subject to the symbolic law is not one that can never be fully satisfied. Like the God of the Old Testament or the Jansenist Dieu obscur, the Other “knows” what it wants from us; it is only we who cannot discern the Other’s inscrutable will. For Lacan however, “the Other of the law does not know what it wants.”

10. This exchangeability involves the ambiguity to the precise causal status of trauma. One is fully justified in isolating the “original trauma” as the ultimate ground triggering the chain-reaction, the final result being the symptom. Conversely, in order for event X to function as “traumatic” the subject’s symbolic universe should have already been struc�tured in a certain way.

11. Cf. Fredric Jameson, Signatures of the Visible, New York: Routledge, 1991.

12. Lacan’s Master Signifier is an “empty” signifier without signified re�ar�rang�ing the previously given content. The signifier “Jew” does not add any new signified. To answer the question “Why were Jews picked out to play the scapegoat in anti-Semitism?” one might suc�cumb to the very trap of anti-Semitism, finding some mysterious feature in them. That Jews were chosen for the role of the “Jew” ultimately is contingent, as shown by the well-known anti-anti-Semitic joke “Jews and cyclists are re�spon�si�ble for all our troubles.”

Why cyclists?—WHY JEWS?

13. J.N. Findlay, Kant and the Transcendental Object, Oxford: OUP, 1968, p. 187.

14. J.N. Findlay, op.cit., p. 1.

15. A simple sym�met�ri�cal inversion brings about an asymmetrical, irreversible, non-specular result. When the statement “the Jew is ex�ploit�ative, intriguing, dirty, lascivious…” is reversed into “he is exploitative, intriguing, dirty, las�civ�i�ous… because he is Jewish,” one doesn’t state the same content another way. Something new, the objet a is produced: “in the Jew more than the Jew himself,” on account of which the Jew is what he phenomenally is. This is what the Hegelian “return of the thing to itself in its conditions” amounts to: the thing re�turns to itself when one recognizes in its conditions

the effects of a transcendent Ground.